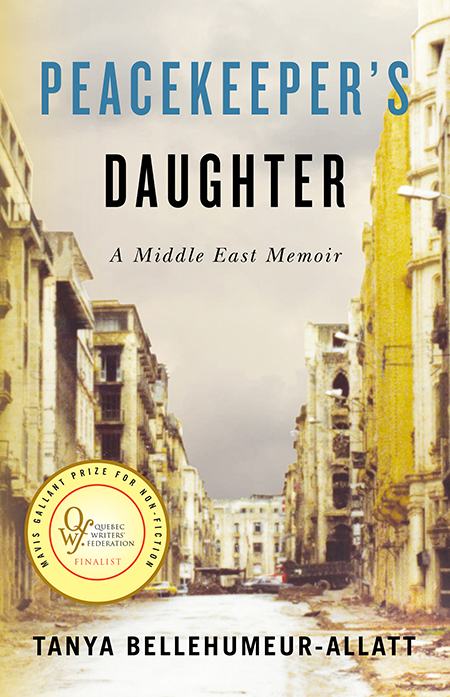

Peacekeeper’s Daughter

I had two small children and was pregnant with our third when my husband called to tell me that a Boeing 767 had crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center. We were still trying to make sense of it when another plane hit the south tower. My children built castles in their sandbox while the world tipped sideways and slipped off its axis. Nearly three thousand people died; six thousand were injured. The president of the United States launched a war on terror.

I had two small children and was pregnant with our third when my husband called to tell me that a Boeing 767 had crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center. We were still trying to make sense of it when another plane hit the south tower. My children built castles in their sandbox while the world tipped sideways and slipped off its axis. Nearly three thousand people died; six thousand were injured. The president of the United States launched a war on terror.

Suddenly the Middle East—where I’d spent a year with my family at age twelve—became enemy territory. My mind spiralled back to Israel and Lebanon in 1982-83 and my father’s mission as a United Nations peacekeeper. In the twenty years since I’d returned, I hadn’t written a word about it. The story was too ugly. But in the aftermath of 9/11, memories surfaced—as vivid as if they’d just happened—and refused to be pushed down.

Until then, in my family’s mythology, our year in the Middle East had been my father’s story. He was the hero, with the rest of us—my mother, my brother and I— revolving around him as his dependents. I’d never dared to betray the traditional narrative and make the story mine. But in those haunting days after 9/11, I wrote in my twelve-year-old voice about the far-reaching effects of war. This became the scaffolding of my memoir, Peacekeeper’s Daughter. Unable to name myself or my fourteen-year-old brother, I wrote with compressed, impressionistic strokes—barely a paragraph for each main event. It felt transgressive and frightening; both an exorcism and a catharsis. Years later, I learned this is a common approach to writing about trauma. We can’t delve into it in detail—it threatens to crush us—but we can jump in and out of the story as if leaping through fire.

Bellehumeur family, Beirut headquarters, 1983.

In the summer of 1982, my family left Yellowknife, where we’d been living for three years, and moved to Tiberius, in northern Israel. This had been decided months before, in the darkness of an Arctic winter, during a time of relative peace in the Middle East. But Israel was now at war with Lebanon and Syria. After repeated attacks between the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Israeli Defense Force, Israel’s goal was to expel the PLO from Beirut. Israelis called the war Operation Peace for Galilee. In Lebanon, it was called "the invasion."

Soon after our arrival in Israel, the president of Lebanon, Bashir Gemayel, was assassinated. In retaliation, thousands of Palestinians were murdered in the Sabra/Shatila refugee camps in Israeli-occupied southern Beirut. The conflict between Israel and Lebanon intensified, as did the Lebanese Civil War. The United Nations called for more peacekeepers in Beirut. My father volunteered. He assumed we would return to Canada or remain in Israel, but my mother refused to be separated from him. “We followed you this far,” she said. “We’re not turning back.”

Over the next seven months, the city fell to ruins around us. My brother and I were students at the American Community School of Beirut, on the campus of the American University and embassy, when a man with two thousand pounds of explosives drove a delivery truck through the embassy gates, killing sixty-three people. An additional one hundred and twenty people were wounded. It was the deadliest attack on an American diplomatic mission since WWII and the first suicide bombing in the Middle East.

On our walk home from school that day, my brother and I detoured around the red Danger tape, picking our way through the rubble.

Peacekeeper’s Daughter: A Middle East Memoir took me twenty years to complete. It’s serendipitous that its release coincides with the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, when the world takes a courageous look back to count its losses and celebrate its heroes. As Margaret Atwood says in The Robber Bride, “War is what happens when language fails.” With violence in Afghanistan increasing and the threat to women and children spiraling out of control, it’s crucial to bear witness; to chronicle the darkness, and any pinpoints of redemptive light, however faint; to use words instead of weapons.

Lt. Col. JED Bellehumeur (retired) and Tanya Bellehumeur

Previously published in The Toronto Star, 2 September 2021.

Tanya Bellehumeur-Allatt is the author of the critically acclaimed Peacekeeper’s Daughter: A Middle East Memoir (Thistledown, 2021), which was a finalist for the Quebec Writer’s Federation Mavis Gallant Award for Nonfiction. Her debut poetry collection Chaos Theories of Goodness was released with Shoreline Press in June 2022. Read more about Tanya’s writing at tanyaallattbellehumeur.com