Canada’s long-standing commitment to peace in the Middle East, and indeed its legacy as a peacekeeping nation, was reinforced in 1964 with the stand-up of the UN Force in Cyprus. Since then, thousands of Canadian soldiers served there, and 28 died. Indeed, a forgotten war in our nation’s history is the 1974 conflict that saw a Greek Cypriot coup d’état and Turkish invasion turn the island into a warzone. Peacekeeping became peacemaking, as two NATO allies were at war with the Canadian Airborne Regiment in the middle (the year 1974 was a deadly time for our military, with casualties in Cyprus and the loss of UN Flight 51 over Syria). Much is written on the heroic actions of our soldiers in 1974; this anecdote looks at Signals and the ‘moxy’ needed to get communications through during that war.

1 Commando Group, about 500 all ranks, with a signal troop of 20 signallers, was in theatre when the Turkish did an amphibious landing near Kyrenia and an airborne assault by the Nicosia Airport. They took the north side of the island, and the Green Line was established, resulting in a wave of displaced persons and village enclaves across the island. The rest of the Regiment deployed from Edmonton, within 96 hours, via Lahr, to Limassol. The Canadian contingent was now 1200 all ranks, reinforced with a mechanized company, a reconnaissance troop, theatre logistics and signals.

Communications for the UN Force, both tactical links to contingents and off-island UN and national rear links, were provided by the UN signal squadron, using primarily British sovereign and Cypriot commercial circuits, most of which were cut when hostilities started.

Signals augmentation from Canada’s 73 Signal Squadron in Egypt included CRATTZ (HF radio, 66 word-per-minute teletype) detachments to provide a national rear link. I remember ordering a 100-foot mast from the NATO supply chain, and incredibly it arrived. British helicopters lifted sections in place as our Linemen rigged the mast and cut long-wire antennae to ‘shoot back’ to Lahr. One day, BGen Beatty, UN HQ Chief of Staff, knocking on the CRATTZ door, demanded to speak to Commander Canadian Forces Europe. The signaller calmly got a radio link and phone patch into the Commander’s office in Lahr.

The Regiment was in the core of Nicosia, at the Airport, patrolling the Green Line and manning UN observation posts (Ops) throughout the sector, sadly taking several casualties, including the loss of Para Berger and Para Perron. From the Ledra Palace Hotel, we watched Turkish 104 jet aircraft bombing east Nicosia, and often took cover behind sandbagged windows from fire fights below. At one point, our barracks at the Ledra Palace and Wolseley Barracks were evacuated under fire.

For Signals, our challenge was huge. The entire fleet of old C11 (HF) and C42 (VHF) sets was being replaced by the ‘new’ AN-PRC 12 family. Renewed hostilities saw OPs overrun and communication equipment lost. A mortar round hit the Signals stores, destroying radios, line, installation kits, antennae and switching equipment. This, along with the influx of radios from Edmonton and Lahr, created a nightmare to sort out kit for repair or wartime strike-off. Helicopter rappel training was essential to deploy and to re-supply our radio rebroadcast sites in the Troodos Mountains. To get communications to a 1 Commando platoon protecting a Turk enclave in the Greek sector, we laid WD1 line over a mile of ‘no-man’s land’ with a Greek machine gun and Turk perimeter guards tracking every move. With the relocation of Canadian troops, a major telephone switched network was put in place. The Linemen earned their hazard pay, fixing lines dug-up or cut by fighting, and repairs done atop poles, often attracting pot shots from nervous combatants.

The 1974 Cyprus war slipped into history as ‘another peacekeeping mission’ during a Cold War era when Canadians had no idea that troops were engaged in combat, taking casualties, and showing the same resolve as at any time in our military history. For the Canadian Airborne Regiment, it was the battle honour that was never awarded. For Signals, it was a remarkable feat of bravery and ingenuity. As a new subaltern, seven months out of training, it was an introduction to action that shaped my ethos as an officer ... train hard, plan for the worse, and take care of the troops ... Shoot, Move and Communicate!

Biography

From Alberta, James Holsworth joined the Canadian Forces in 1969, attending Royal Roads and Royal Military Colleges to graduate in electrical engineering. His first posting to the Canadian Airborne Regiment included a tour in Cyprus during the 1974 war. James served as a signal officer in Germany 1976 to 1981, with 3 Mechanized Commando, The Royal Canadian Regiment and 4 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (CMBG) Headquarters & Signal Squadron.

He studied French, then worked in Army Headquarters (HQ) in Montréal and attended the Army Staff College in Kingston. As a major, he remained at Army HQ to write electronic warfare doctrine and coordinate signal operations, later attending Staff College Toronto. James returned to Germany to command 4 CMBG HQ & Signal Squadron and was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel to work in Ottawa on the Army staff in command information systems. From 1991 to 1996, he commanded the 1st Division HQ & Signal Regiment and then instructed at the Army Staff College.

Upon promotion, Colonel Holsworth was appointed Director of Signals in Ottawa, then Director of the Technical Staff Programme at RMC. In 1999, he went to Bosnia as Chief of Signals in the NATO HQ. In 2004, James completed three years as Canadian Military Attaché, and Director with the America, Britain, Canada, Australia (ABCA) Programme, in Washington, DC. He returned to the Joint Staff as Director J6, responsible for information operations and strategic communications, before retiring in 2005, ending 36 years service.

James worked as a defence consultant, directing an advance military command and control course, completed his master’s degree in Defence Management & Policy, and was appointed Colonel of the Regiment for the Joint Signal Regiment. He has served on the Board of Directors of Kingston General Hospital (KGH), University Hospitals Kingston Foundation, Military Communication & Electronics (C&E) Museum Foundation, and Hospice Kingston, and was Chair of the KGH Foundation, Kingston Commissionaires, and C&E Heritage & Museum Committee. He organized battlefield studies to Vimy, Normandy, The Netherlands, and a reunion of comrades in Cyprus in 2024.

James is married to Anne St-Pierre, a retired military and career labour & delivery nurse. They have three children: David a military engineer, Julie a teacher, and Jonathan a signal officer ; and six grandchildren. He is an avid skier, traveller, historian, and grandfather.

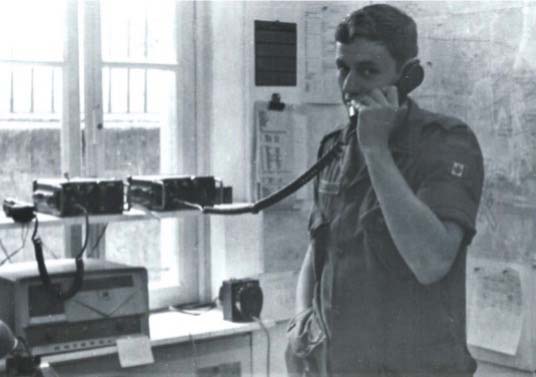

Lt Jim Holsworth, Cyprus 1974.

Lt Jim Holsworth, Edmonton 1975.