Talking my way out of armed confrontations and police shakedowns in Congo and leaping away from a vehicle trying to run me down in Sudan are nostalgic. Such events pale in gravity and scale to notable issues in DRC which deserve analytical reflection.

Champions of peacekeeping cite successes in places such as Bosnia-Hercegovina (BiH), Cambodia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mozambique, Namibia, and Tajikistan together with Côte d'Ivoire, Liberia, and Sudan, but seldom state their reasoning. Critics of peacekeeping cite failures in Cyprus, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and throughout the Middle-East, noting such issues as host-nation corruption, insufficient political will, institutionalized inefficiency, and self-service, all symptoms of systemic challenges. Yet, neither viewpoint assesses root issues shaping missions' outputs and outcomes, and both overlook one rule of geopolitics: 'in the land of diplomacy, context is king.' To inform future peace operations, the following diagnostic analysis of DRC identifies impacts and constraints of two context-shaping root issues - law, and politics. They become even clearer when contrasting DRC with BiH and Sudan.

Legally, treaty-based international organizations (IOs), such as the African Union (AU), International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), International Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), OHR and UN, exercise powers only as delegated or implied by Member States. Procedurally, the UN Charter provides its aspirational object and purpose, "…maintain international peace and security…" The Charter does not provide for 'how' peace and security is to be gained and sustained, save Chapter VII Security Council 'binding decisions.' Preambular and operative clauses of Council Resolutions provide for programs and practices to enable parties to the dispute to conclude and sustain peace. UN organs and agencies and humanitarian organizations infer operational guidance from resolutions and undertake to provide the 'how' on a best-efforts-basis. Yet, these bodies only enable principal parties to the dispute to settle that dispute. Interpreting this process as any obligation of the UN et al to deliver international peace and security as a fait accompli outcome has no basis either legally or politically. As enablers of peace operations, these bodies collaborate iteratively with parties to the disputes, but the parties themselves retain prima facie responsibility for establishing framework conditions in which enabling peace operations may succeed.

Within constraints of treaty and international institutional law and fact-based realpolitik, the Dayton Peace Accords (1995) provided for the OHR to successfully facilitate their execution in BiH, supported by the 55-Member-State Peace Implementation Council. The IGAD successfully mediated the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (2005) between parties to the dispute in Sudan.

Disputes in the DRC were settled through several peace agreements: Lusaka Ceasefire (1999), Sun City (2002), Pretoria (2002), Luanda (2002) and Global and Inclusive (2002). The agreements were secured with the assistance of the AU and ICGLR. Yet, context sabotaged sustainable peace. Context comprised (i) dissatisfied regional ethnic/clan-based militias excluded from peace processes; (ii) inadequate Security Sector Reform within the DRC enabling break-away military factions to gain standing as Other Armed Groups; (iii) armed incursions by neighboring states across undefended/able borders to advance ethnic and regionally political agendas inside DRC during its formative years of stabilization; (iv) third-party states' rampant exploitation of DRC's natural resources; (v) international donor fatigue. Diagnostic analysis suggests the context of regional socio-political anarchy sabotaged sustainable settlement of DRC-centric disputes. Prescriptive analysis suggests Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda must substantively respect the sovereignty of DRC's borders and implement effective Security Sector Reforms.

Politically, three centers of gravity of successful peace operations must be extant. First is possession by parties to the dispute of bona-fide wills to invoke sustainable peace, whether arising from war fatigue or political opportunism. This subjective element symbiotically empowers the objective element of a (tentatively) negotiated peace agreement. Second is the belief of the host nation's populace — governors and governed — that IOs have sufficient capacity to enable parties to the dispute and the host nation's civil society to sustain peace. Third is the belief of the IOs that their capacity to enable same is sufficient. Together, the second and third centers of gravity synthesize a mutually inclusive confidence. Conditions precedent for the latter are (i) full comprehension by IOs of the host nation's socio-cultural norms; (ii) realistic understanding by the host nation of IOs' capacities.

In sum, future success in peace operations rests on appreciation of three issues. Firstly, abuse of sovereign power by, and neglected reforms within adjacent and regional states elevated the DRC' crisis to a supra-regional if not global matter. IOs lack legal and political resources to fill such power vacuums at scale. If left unsettled, ensuing issues will gravitate beyond, viz., current unlawful migration from African to European states. Secondly, such abuse, if repeated, will heighten the intractability of complex emergencies and increase demand on limited pacific means to settle same. This invites use of 'countermeasures employing lethal force to restore the status quo,' leading to humanitarian tragedy but not internationally wrongful acts. Thirdly, IOs, agencies, and implementing partners must incorporate fulsome coherence of local socio-political norms in planning, risk-assessing and executing peace operations; anything less guarantees mission failure.

Biography

Joe Howard's experience in peacekeeping began later in life. It succeeded a Calgary-based twenty-five-year practice in Chartered Accountancy concurrent with seventeen years as a commissioned officer with the King’s Own Calgary Regiment (Royal Canadian Armoured Corps), Canadian Armed Forces Primary Reserve.

It started in 1999, with an invitation to attend the UN Military Observer Course at the Peace Support Training Centre, Kingston. An offer followed in 2000 to be one of the first two deployed under OPERATION CROCODILE. This orchestrates Canada's deployments to the United Nations' (UN) peacekeeping mission in Democratic Republic of the Congo, (DRC), Mission de l’Organisation des Nations Unies en répubique démocratique du Congo, (MONUC). MONUC and its successors feature among the UN’s repertoire of larger peace operations under Security Council Chapter VII Resolutions. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees classifies DRC's situation a 'complex emergency.' Appointed Deputy Chief Plans while headquartered in Kinshasa, the position required country-wide reconnaissance and planning of initial deployments of battalions and Military Observers from e.g., India, Nepal, Pakistan.

Returning from DRC, a short-notice request came from National Defence Headquarters, Ottawa, to serve as Balkans Theatre Desk Officer, J-3 International Operations (Tim Grant, Chief of Staff) immediately following 9-11. This facilitated a deeper appreciation of NATO peacekeeping and of the Operational Planning Process concerning OPERATION APOLLO.

In 2001, training began in Civil Military Cooperation. 'CIMIC' is a military-led function influencing cooperation of civilians and humanitarian organizations with peacekeeping forces in conflict zones. Being 'hearts-and-minds military diplomacy,' it leverages formed bodies of armed troops in facilitating dispute settlement and post-conflict socio-economic development.

In September 2002, secondment to the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Second Battalion Battle Group (Mike Day, Commanding Officer) preceded 2003 deployment to Bosnia-Hercegovina (BiH), the twelfth rotation in Canada's OPERATION PALLADIUM supporting NATO's Stabilization Force (SFOR). The Office of the High Representative (OHR), a multilaterally supported political structure emanating from the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords, partnered with SFOR in co-managing national civil-military programs.

Appointed Chief CIMIC and Senior Liaison Officer while headquartered at Zgon, 97 km southeast of Bihać, the position included sourcing opportunities for the Battle Group's assisting local government and humanitarian agencies, advancing rule of law and civic reform, and disbursing Canadian funding on infrastructure projects.

Returning from Bosnia, invitations to attend the UN's Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Staff Course, Geneva, and U.S. Naval Post Graduate School's Civil-Military Relations Course, Monterey, as a private citizen expanded peacekeeping skillsets. These facilitated civilian consultancies in 2004 with U.S.' Defense Security Coordination Agency introducing CIMIC to Albanian and Romanian armed forces.

Returning to military venues, a 2004 invitation to join the Standing High Readiness Brigade for UN Operations, (SHIRBRIG), (Greg Mitchell, Commander), led to deployment in 2005 to the UN Mission in Sudan, (UNMIS), under Canada's OPERATION SAFARI. Under multilateral political leadership, SHIRBRIG as a military headquarters collaborated with the UN Secretariat to hasten deployment of peacekeeping troops through advancing operational planning.

Training with multinational staff officers at SHIRBRIG Headquarters, Høvelte Barracks, Birkerød, Denmark and UN Headquarters New York emphasized Civil-Military Coordination, (CMCoord). Unlike robust 'cooperation' in CIMIC, OCHA's CMCoord tempers 'coordination' to separate humanitarian from military operations. Humanitarians must be (seen) as 'neutral and impartial.' Hence, cooperation with any military may undermine this perspective as military forces are often (perceived as) root sources of humanitarian crises.

Appointed Deputy Chief CMCoord and acting Chief Military Plans while headquartered in Khartoum, the position required deconflicting jurisdictional claims of UNMIS' humanitarian and military components, sourcing opportunities to collaborate with civic organizations, and planning initial deployments of battalions and Military Observers.

Returning from Sudan, a 2006 offer of a civilian consultancy at UN Headquarters New York concluded with assessing peace operations in Ghana and Liberia. Subsequently, an academic appreciation of peacekeeping within geopolitical frameworks begged an MA in international studies and diplomacy at the School for Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Civilian consultancies at UN headquarters followed in 2008–09, leading to assessing peacekeeping in Côte d'Ivoire, DRC, Liberia and Sudan.

To appreciate peacekeeping with sharper discipline, an LL.M. (Advanced) in international criminal law at Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, followed in 2009–10. In 2012, competence in geopolitical legality begged a six-year PhD at China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, researching international humanitarian law framing peace operations. Currently, research and lecturing on international law and peacekeeping informs Canadian and Chinese audiences pending further consultancies.

Canada's Minister for international Cooperation, Susan Whelan, PC, MP, being welcomed to Drvar, BiH by Chief CIMIC and Senior Liaison Officer. Second Battalion PPCLI Battle Group 10 May 2003, accompanied by Colonel Greg Gillespie, Commander Task Force Bosnia and Hercegovina.

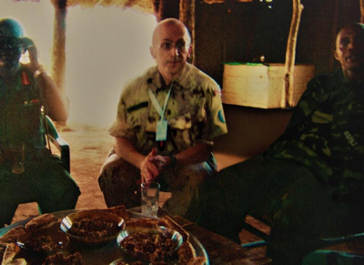

Engaging Sudanese People's Liberation Army Brigade & Battalion Commanders, Kirmuk, Sudan, July 2005.