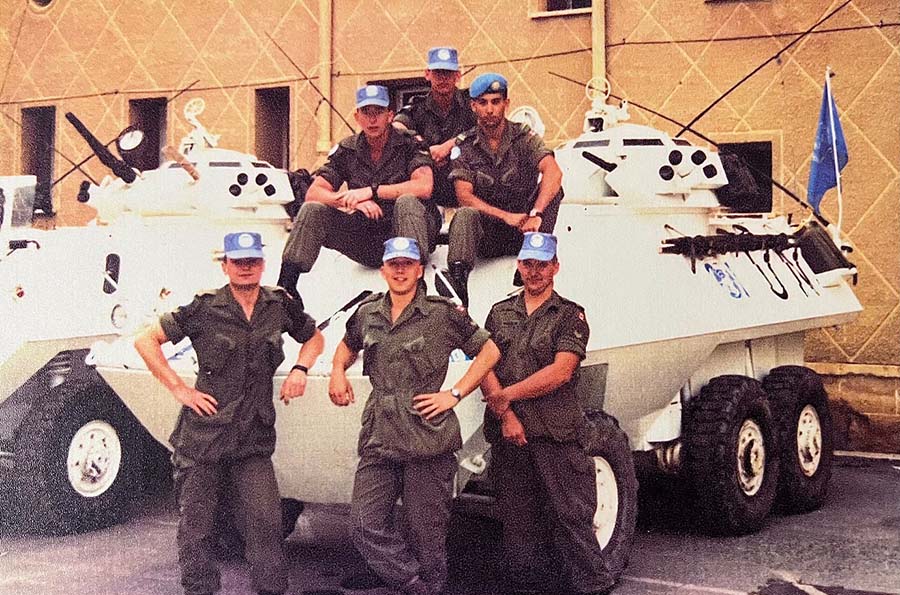

The stories I am about to tell you took place during my deployment to Cyprus in 1992 as part of the United Nations (UN) Operation Snowgoose 57. This operation was essentially a peacekeeping operation between the Turkish Cypriots and the Greek Cypriots since the Turkish army invaded Northern Cyprus in 1974. To do this, a 180-kilometre long "buffer zone" cuts the island of Cyprus in two, and this zone is controlled by UN peacekeepers. So, I was sent there on a peacekeeping mission with the 3rd Battalion of the Royal 22e Régiment. I was a lieutenant at the time and was deployed as an infantry platoon commander with Rural Company, as well as to company headquarters as an administrative officer.

After spending nine months in Labrador under the NATO umbrella, I was happy to be able to go on a UN mission and proud to wear the blue helmet abroad. What's more, the Cyprus operation was the only major Canadian Forces operation at the time. But as soon as I arrived, I became disillusioned. Many of the rules set by the top decision makers at the UN in New York did not make sense to me. First, as members of the UN, we should have had complete freedom of movement within the buffer zone. However, there were roads that we were not allowed to use, even though we could access them from the Greek side, dressed in civilian clothes. Inside the buffer zone, everything was frozen in time, so we were not allowed to touch anything, not even a brick that had been there since 1974.

There were also rules that were too restrictive and that put the lives of the soldiers on the ground at risk. I personally experienced a direct threat to my life during this operation, despite the fact that it was considered "quiet". Together with my platoon second-in-command, Sergeant Fournier, we had approached a Greek military post at around 1 a.m. We disembarked from our vehicle and went to the front. On seeing us, the soldier drew his weapon and pointed it at us. We saw that he was intoxicated. The soldier started shouting in Greek, and of course we couldn't understand him. We answered him: "U-N, U-N", to make it clear that we were members of the UN, avoiding of course any false move, which could have triggered a shot. In the end, we managed to retreat. But if we had to defend ourselves against an attack, we were not equipped to do so. Indeed, the United Nations prohibited us from carrying a loaded weapon. Another 'nonsense' in my eyes.

During this operation, we also had to adjust to the great differences in behaviour between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot soldiers. On the one hand, an army with little discipline (as the drunken soldier testifies), and on the other, an army that fears reprisals from its superiors. When we approached the Turkish posts, the soldiers, often young, were afraid of us, until we told them that we were Canadians and present in Cyprus to keep the peace. Then it was possible for us to fraternise with them.

In summary, I still believe, despite my mixed experience in Cyprus, that the purpose of the United Nations remains positive and laudable. But are the rules and decrees dictated by the UN's top leadership always appropriate to the reality on the ground? Several colleagues experienced similar frustrations in Bosnia when they had to comply with no less than 26 rules of engagement. Keeping the peace, yes. But at what cost. And above all, in what context. The military need support in their often difficult and complex missions. Putting unjustified obstacles in their way is certainly the best way to provoke their disengagement.

Biography

I joined the Canadian Armed Forces after graduating from high school in 1987, as an infantryman with the Régiment de la Chaudière. My reserve regiment is part of the 35th Canadian Brigade Group and is recognized for, among other things, its outstanding participation in "D-Day" on June 6, 1944, during the Normandy Landings in France. I have always been proud to be part of the Régiment de la Chaudière, which I had the honour of commanding for four years, from 2003 to 2007. In June 2004, I participated in the celebrations of the 60th anniversary of D-Day, where four monuments in as many towns and cities in Normandy were inaugurated to pay tribute to the courage of the "Chaudières" who helped liberate France from the enemy. In many ways, these were moving celebrations that reminded everyone how essential the military presence is in the outcome of conflicts.

Before becoming commander of the Régiment de la Chaudière, I obviously trained as an infantry officer and progressed to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. I am also a graduate of the Canadian Armed Forces Command and Staff College, as well as the École militaire de Paris. In 2002, France asked Canada to send me as an instructor on a specialist staff officers' course; a first in the history of the French reserve. During this course in Paris, I had the honour of training French, British, German, Swiss, and Canadian reservists.

In May 2006, as part of my duties as Commander, I was granted a private audience with Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace. This audience gave me the opportunity to hand her the reprint of a book on the history of the Régiment de la Chaudière and to speak with the Colonel-in-Chief about her regiment.

During my 22 years of military service, I carried out two operational missions: the first in Goose Bay, NL, under the aegis of NATO, and the second in Cyprus, for the United Nations, with the 3rd Battalion of the Royal 22e Régiment. I served as a platoon commander for the rural company and as an administrative officer at company headquarters.

I retired from the Canadian Armed Forces in 2009. In parallel to my military career, I obtained a degree in political science from Laval University. I then worked in the business world. In 2015, I was elected Member of Parliament for the riding of Charlesbourg-Haute-Saint-Charles (Québec City). In this capacity, I was appointed Associate Critic for National Defence in the Official Opposition Shadow Cabinet (2015–2017) and Shadow Cabinet Minister for Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness (2017–2020). I also served as Vice-Chair of the Defence and Security Committee of the NATO Parliamentary Association (2016–2019). Thanks to my experience in the military world, I am regularly consulted on all issues related to defence and national security.

With Warrant Officer Martel (right), near an observation post in the buffer zone in Cyprus.

At the front: Corporals Patrick Raymond, Alain Desrochers and Yoland Maheux. On the vehicle: Corporals Luc Lemay and Brian McDougall, and Lieutenant Pierre Paul-Hus.