Saint John, NB, Canada

Wayne J. Buck

Current Location: Norfolk, VA, United States

The Sahara Desert is a remarkably interesting place. If you have never been there you would think it empty and barren. Nothing could be further from the truth. At one time the desert was at the bottom of the ocean which makes for remarkably thought-provoking geographical features including lava outcrops, sinkholes, and low mountains. The people who live there are very tribal and usually live in tents in family units. Sahrawis are composed of many tribes and are largely speakers of Arabic. Interestingly, many also speak French due to Moroccan influence, and Spanish due to the influence of Cuba. It was Cuba who taught the Saharawi to fight, and from where they got their weapons.

In Peacekeeping Operations, it is somewhat normal for Canada to send formed units to the conflict. For the Sahara, Canada chose to send up to 35 individuals who would support the mission as required. I was one of those who deployed for a year. The disputed area is divided by a tall berm. Morocco is on one side and the Saharawi on the other. My first job was as a teamsite leader of 15 multinational military members on the Saharawi side in a place called Dougaj. My boss was a Chinese Colonel who was in Dakla about a five to six-hour vehicle ride away. That was also where the closest telephone was located. All our work was done by radio and that included calling home once a week through a civilian operator. We lived in tents and patrolled the area looking for either side not adhering to the agreed cease-fire. In the team were several nationalities including Columbian, Polish, Canadian, Brazilian, British, and Argentinian. This was a dual-language mission with English and French as the working languages. The funny thing is when Argentina volunteered to be part of the mission, they chose to teach their Spanish speaking officers French. That was fine except everyone else only spoke their native language and English. Only I had a clue what the Argentinian was saying. So, I became an impromptu English language teacher for a few months.

As you may expect, the desert is hot. The temperature never really got below 30°C and usually was around 35°C. Once it was 60°C for three days in a row. It was so hot that the oil in our aircraft got so thin that the electronics would not allow the aircraft to start. It thought that there was no oil. We needed to spray water on the engines to cool them down. Even in the heat there is still wildlife and domestic animals. I was told that there were fox and rabbits, but I never saw any. I did see lots of scorpions and snakes. The most dangerous snake was the horned viper whose bite would kill a child and certainly make an adult extremely uncomfortable.

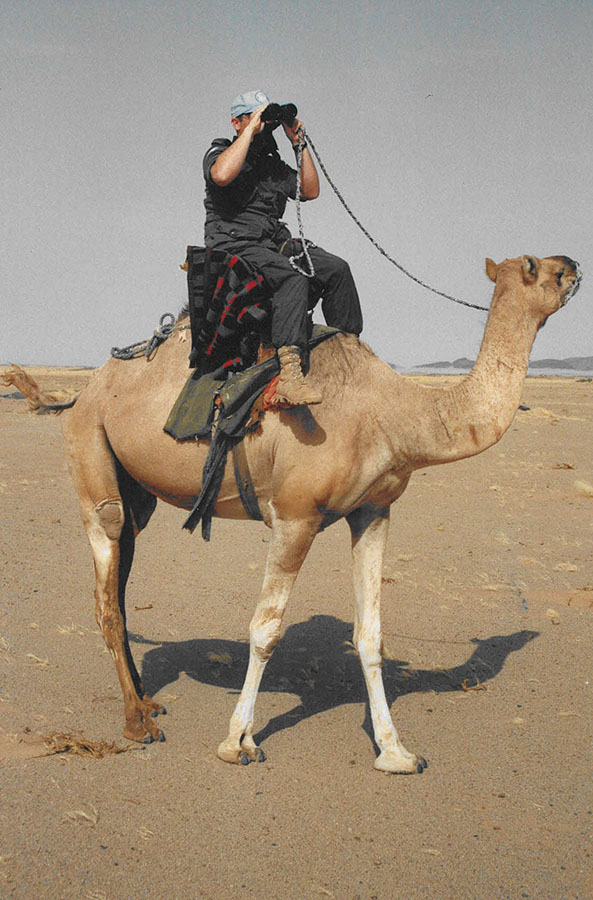

The local people were nomadic and frequently moved from place to place. Certainly, a family was considered rich if they had more than two camels and a few goats. Sometimes we would borrow the camels if we had to go into especially soft sand areas where our Toyotas could not go without sinking. While on patrol looking for ceasefire infractions, we often visited the locals. In the tents while talking (through a translator) we would be offered camel milk. It came in a large bowl which everyone drank from. It was very sour so if we knew that we would be visiting a tent, we would bring five pounds of sugar as a gift. The locals knew that meant to put the sugar in the drink and that made the drink edible for us.

After about four months in Dougaj, the sector commander asked me to become teamsite leader of a camp called Awsard. This camp was much larger and on the Moroccan side. I took the job and essentially administered the Southern Sector. I had my own medical airplane and resupply helicopter along with about 40 staff for patrolling and administration. I kept that job until I went home eight months later.

Biography

I genuinely enjoyed my 29 years in the Canadian Forces. I started at age 12 in Air Cadets which is not actually a part of the Canadian Forces, but it surely exposes you to a lot of military related experiences. Later I joined the Signals reserves and enjoyed that experience even more. As a member of 722 Communication Squadron in Saint John, NB, I trained as a radio operator and teletype operator. Teletype was like an old-fashioned Internet without pictures. While attending the University of New Brunswick, the military asked me to join the regular force as a Signal Officer. In 1983, with a computer science degree and having finished my signal officer training, I took command of a signal troop within 1st Canadian Signal Regiment in Kingston, ON that specialised in microwave transmission. A true highlight of my career. I was surrounded by exceptional young men and women who performed well during operations and exercises and gave their all to the job. I was to find out that this was only normal in the Canadian military.

A year later I was the Signal Officer for 3rd Regiment Royal Canadian Horse Artillery in Shilo, MB. There I also commanded a troop and was Signals advisor to the Commanding Officer. It is also where I took my new wife in 1986 and we had a heck of a good time in the middle of the prairies. Military postings are what you make of them. We square danced, did woodworking, curled, golfed, and took part in a highly active mess life. We also travelled locally while seeing many things that most Canadians do not even know exist; for example, the Boissevain, MB turtle races or the snowmobile swamp skimming championships.

In 1992, I was selected to be a peacekeeper in the Western Sahara Desert as part of MINURSO, the United Nations Mission for The Referendum in Western Sahara. This was a great experience but more of that on the previous page.

After receiving a master’s degree from the Royal Military College in 1996, I was posted to National Defence Headquarters. Soon after arriving there, Canada was asked to lead a mission in the Great Lakes Region of Africa where there was a fear that several hundred thousand refugees had gone missing and were in danger. Operation Assurance was launched and I was sent to be a member of the Signals team. We staged out of Stuttgart, Germany from the U.S. base there. Once ready, we deployed to Uganda and set up initially at the Entebbe airport. After a short time, we moved to an unused fairground which had enough room for vehicles, satellite dishes, and so on. Eventually, the lost refugees were found, and the mission wrapped up much earlier than expected.

After Ottawa, I commanded 2 Area Support Group Signal Squadron in Petawawa, ON. We were responsible for all strategic military communications in Ontario and heavily involved in Operation ABACUS, the name given to the possible Y2K disruption. For more than two years we tested equipment, re-wrote software, and did all that we could to ensure that all systems, military and civilian, would keep working past 31 December 1999. In Petawawa, we were essentially in lockdown on New Year’s Eve. No parties, be prepared to move to where and when needed, and ensure personal and family safety. In the end, our work paid off. The country prepared well and Y2K was a non-event.

After a year at Staff College in Toronto, my family and I moved to the NATO headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia. My Canadian military training and experiences prepared me well for this assignment. The work was in some ways technical, in some ways managerial, and in many ways innovative. In 2005, after being in Norfolk in uniform for four years, I became a NATO International Civilian (essentially a civil servant) as a specialist in modelling and simulation. We have now been here for 20 years and have formed strong friendships with many international colleagues and I enjoy every day when I go to work.

The military tradition continues in the Buck household. Son Alex is a Major in The Royal Canadian Regiment and has deployed to Afghanistan twice and to the Ukraine, as well as having been an exchange officer with the U.S. Army.

The Russian Mi-8 (Hip) did extremely well in the desert and is now used by over 50 countries around the world for a variety of roles. This shot shows Wayne guiding his helicopter to its resting location. Taken in 1993 at Awsard by unknown photographer.

Camels were used for patrolling when the sand was too soft for motor vehicles. Taken 1992 by unknown photographer.